Harold Coyle broke into the literary scene with his techno-thriller novel Team Yankee in 1987, which quickly became a New York Times bestseller. “Coyle’s unusual skill as a novelist brings to life the realities of combat as very few writers are able to do. I found it absorbing, exciting, and was literally unable to put it down,” writes author W.E.B. Griffin on Team Yankee. This book was followed by other works of speculative military fiction as well as historical novels set in the French and Indian War, the American Civil War, and, more recently, World War II.

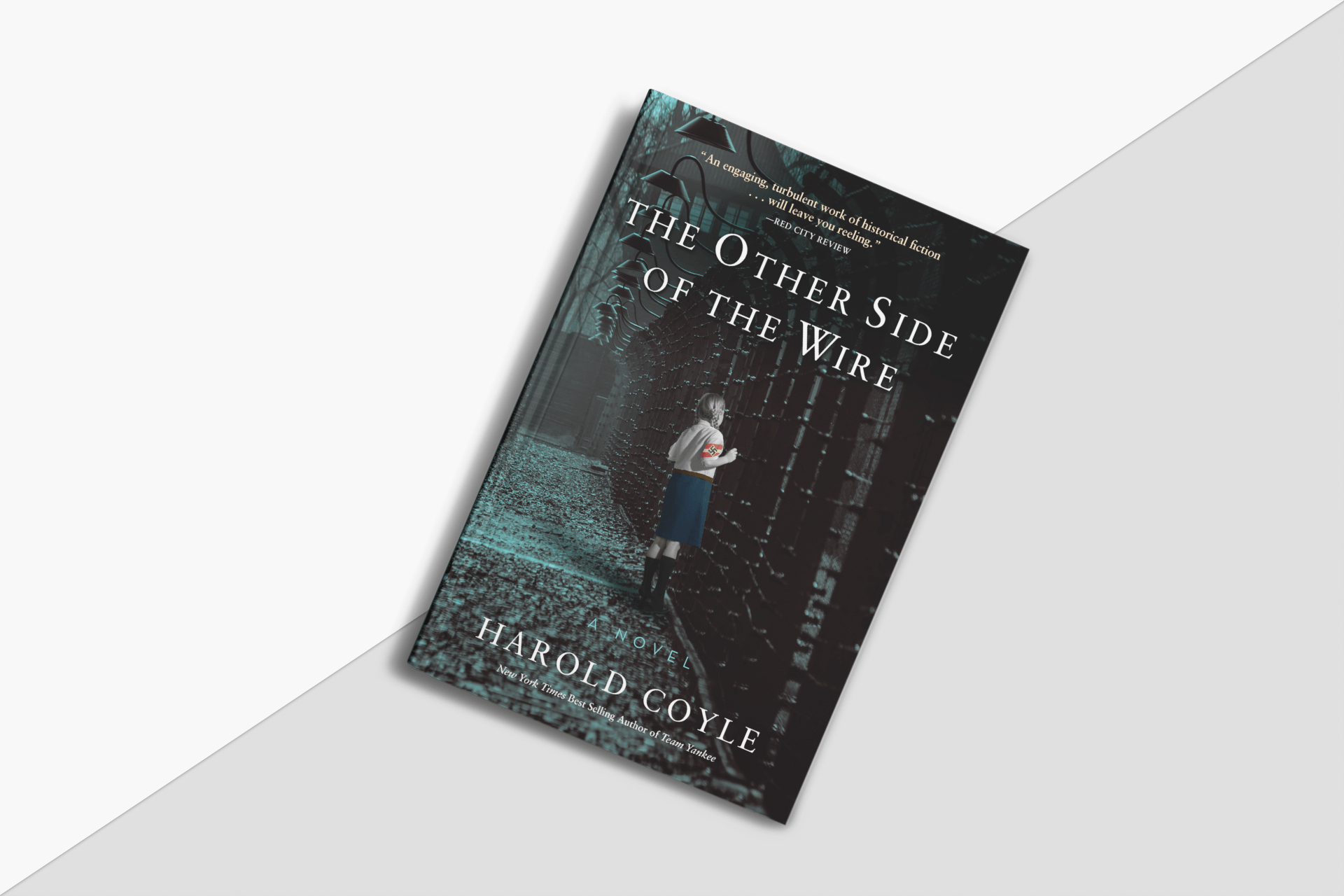

The author’s latest piece of work, titled The Other Side of the Wire and published by Master Wings Publishing, is a thought-provoking, historical fiction book that not only tells an empathetic coming of age story, but also delivers on Coyle’s thorough research of the time period.

To give you an inside look into the author’s new books and the characters you will encounter, we interviewed Harold Coyle. Learn more about his process as an author and why this should be the next book on your list below.

What motivated you to write this book? How did this story first come to be?

Two films, Europa, Europa and The Boy in the Striped Pajamas caught my interest, in that they presented storylines that were unique and compelling.

Europa, Europa is the true story of Solomon Perel, a German Jew who survives the Holocaust by being adopted by a German army officer and assuming the guise of a dedicated member of the Hitler Youth.

The Boy in the Striped Pajamas is a fictional story that tells the story of the Holocaust through the eyes of a camp commandant’s eight-year-old son who befriends a Jewish boy interned in his father’s camp, ignorant of what goes on in the camp or the fate that awaits the boy in the striped pajamas.

What did you learn when writing the book? Did anything surprise you?

Three items stand out.

The first was just how important the families of men responsible for the Holocaust were to them, for they provided them with the social support they needed that allowed sane, rational men to cope with what they were doing in the camps. While the men did their utmost to shield their families from the horrors they were perpetrating, the adult members of the families went to extremes to either avoid finding out what was going on in the camps or pretend it was not happening.

The second was just how involved Adolf Eichmann, and by extension, the Nazi Party, was in attempting to coerce and, to some extent, aid in the emigration of German and Austrian Jews to Palestine under the Haavara Agreement, which was an agreement between Nazi Germany and Zionist Federation of Germany.

The final item concerned the early effort in the field of gender reassignment. Contrary to popular beliefs, gender reassignment was being aggressively pioneered by Dr. Ludwig Levy-Lenz, a gynecologist associated with Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexology in Berlin between 1925 and 1933. He performed the first known male-to-female reassignment surgery on Dora ‘Dorchen’ Richter in 1931. Even more surprising was the fact Levy-Lenz was allowed to return to Berlin in 1936 as part of the Nazi Party’s effort to stifle anyone’s concerns about what was going on in Germany during the run-up to the 1936 Olympics. Of course, when the games were over, Levy-Lenz was once more banished.

Was the main character inspired by a real person? If so, who?

Solomon Perel, a German Jew born in 1925. In 1935 his family fled Germany to Lodz, Poland when Perel was ten after the shoe store owned by his father was pillaged and he was expelled from school. Through a series of misadventures that prove fact is, indeed, stranger than fiction, Perel was adopted by a German Army officer and became a member of the Hitler Youth. After World War II, Perel immigrated to Israel where he fought in the 1948 Israeli war for independence and, after the war, became a businessman.

What advice do you have for aspiring writers?

Write what you know and when the story is ready to be written.

What are you reading currently?

Tower of Skulls: A History of the Asia-Pacific War, Volume I: July 1937-May 1942 by Richard B. Franks. I am also listening to the audiobook Waterloo: The History of Four Days, Three Armies, and Three Battles by Bernard Cornwell when exercising.

Do any authors/titles have a strong influence on your writing?

James Michner and Shelby Foote, both of whom possess a narrative style that does not get in the way of the story.

What did you edit out of the book?

In an effort to maintain the focus of the story on Hannah and what she saw and experienced, I intentionally avoided any depictions of what occurred in the camps. The closest I come is in Chapter Nineteen when Madam Delome tells Hannah and Frau Sanders what she does in the camp.

What is your writing process like?

For lack of a better way of describing it, it is episodic. When a story is ready to be written, I write it, usually between the hours of 2:00 AM and 7:00 AM when the house is quiet, and I am rested. Intellectually, I’m pretty much a basket case after 12:00 noon, good only for feeding the animals here on the farm or mowing the lawn.

What was the hardest scene for you to write? Why?

Chapter Twenty, The Report. All items listed in the report mentioned in this chapter were lifted, verbatim, from ‘The Frank Memorandum’ dated 26 September 1942, issued by August Frank of the SS Main Economic Administration Office. The cold, dispassionate manner with which they were enumerated is, to me, disquieting, for each of those items meant something important to the person they were taken from. This was especially true of the gold teeth, brutally yanked from the mouth of corpses, and prams that once carried infants who were no more. Even now, the mere thought of this subject evokes a strong emotional response within me.

What life experiences have shaped your writing the most?

Writing the concept of operations that is found in paragraph 3, Execution, of the U.S. Army’s standard operations order. Seriously. In laying out how subordinate units will carry out an intricate combat operation, from start to finish, is not as easy as it sounds, especially when the people reading it are usually sleep-deprived, short on time, under pressure, and expected to carry out their role in the forthcoming operation on their own. Get it wrong or do a poor job, and the consequences, are immediate and consequential, even during training exercises.

Can you share any thoughts you might have on the character's lives post the novel? Hannah’s childhood friends, or Horst?

In 1956 the West German government estimated that 570,000 German civilians died in World War II from all causes. If they survived, the lives of Hannah’s friends, Sophie and Gretchen, could easily have followed several, very different paths. Some Germans were virtually untouched by the war, either because they lived in small rural villages that were not on Bomber Commands target list or they were part of a family that were able to escape to secluded retreats in the Alps. Others were far less fortunate. 3.6 million homes out of sixteen million homes in 62 cities were destroyed, rendering 7.5 people homeless. To alleviate this problem, Allied powers in both East and West Germany ordered all women between fifteen and fifty to participate in post-war cleanup. These women came to be known as Trümerfrau, or ruins women who worked nine hours a day, earning 72 Pfennigs an hour. Another, less savory path to survival was prostitution. A lucky few, some 20,000 between 1945 and 1949, married American servicemen and emigrated to the United States as war brides.

Horst was a survivor. He became an ardent Nazi in order to escape the persecution of men like him suffered under the Nazis. In the immediate wake of the war, he would have fled Germany via the ratline, popularly known in literature and the Odessa organization, or ingratiating himself with the Western Allies occupation authorities by working for them in some capacity. In time, he would become a lawyer or a bureaucrat with the West German government in Bonn.

Wolfgang, raised by his grandparents, would go to college and become a professional of some sort, possibly an architect. He would spend the rest of his life revering his father, working with other children of high-ranking Nazis to rehabilitate Ernst’s memory and joining others who sought to deny the Holocaust ever happened.

Why should people read this book?

The Other Side of the Wire is a cautionary tale. Nelson Mandela said, “Our children are our greatest treasure. They are our future. Those who abuse them tear at the fabric of our society and weaken our nation.” This abuse can come in many forms. In the case of Nazi Germany, the entire educational system was structured to separate Germany’s youth from the traditional values that had made Germany a culturally and intellectually advanced society, replacing it with an ideology driven by hatred and blind, unquestioning obedience.

The ease with which the German youth were seduced by the Nazi leadership is a story that cannot be ignored, for it is happening again in various parts of the world today. As Hitler himself stated in a speech on November 6, 1933, “When an opponent declares, ‘I will not come over to your side,’ I calmly say, ‘Your child belongs to us already. . . . What are you? You will pass on. Your descendants, however, now stand in the new camp. In a short time, they will know nothing else but this new community.’”

To pretend things to be otherwise is to condemn future generations to the horrors and suffering our forebears endured. To me, that would be a crime that makes what the Nazis did all the more terrible.

Click here to order your copy of The Other Side of the Wire, a Master Wings publication, today!